Clúnath

This article contains broken media.

This may mean that some content shown here might not display correctly, or at all. |

| Clúnath | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hunnán Hwallt-or-Mynyd, one of Nwngan Dydd's husbands | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. clunicus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cornuvaelus clunicus | |

Clúnydd (Cornuvaelus clunicus (SG: Clúnath) Phyrean: Clúnath; Ascon: Kluned; Classical Nanai: 角人 kɨokH ɲeH “horned person”) are large feld-like mylls. They are theorised to have originated around Northern Phyrea, in the forests of southern Amrhyl, though nowadays they're spread all around the globe. They resemble felds with unusual cold-hued fur, and magenta skin and flesh. Most clúnydd have at least one pair of black or bluish horns, and some retain one pair of vestigial ear-shaped ornaments, called the auricula. These cannot be used to hear, instead their historical function was to sense climate and other atmospheric conditions.

They're omnivorous (though historically carnivores, not unlike felds). Despite popular belief and folk descriptions, clúnydd were never known to feed on felds. They are the only known sapient mylls.

Clúnydd worldwide have largely been stigmatised for their appearance, often with basis on local folklore and fearmongering. This has historically made them recede into less urban areas. In recent years, though, as these stigmas become less prevalent, they have been better able to integrate within the areas they were originally forced out of. Historically, clúnydd were cave-dwelling, and they still retain this aspect somewhat in the modern day. Much of clúnath architecture is based around large tunneling underground homes and even settlements.

They are also known by the name (a)breggan, although this term is nowadays considered a slur, along with its variant breg or brig. Another name for them before the adoption of clúnath/clúnydd was cwllwyl.

Etymology

Clúnath and its plural clúnydd reached Phyrean through Classical Darsavian клѵнаѳ, a loanword from Old Hotgodian kluxu nasü (xruunar in modern Hotgodian), literally "local person" (as the Hotgodic languages are Clúnath languages).

The Phyrean brwchwyl, the origin of the word breggan (and thereby an offensive term), stems from the Common Phyric *breux vuel, “death feld”, each word respectively from Proto-Namuno-Ethian *brewh₁(e)s "death" and *bʰwelos "feld, person, individual." Cwllwyl is a contraction of cwllyd “black, dark” and fwyl "feld, person," stemming from the fact that the vast majority of phyrean clúnydd have dark fur tones.

Biology

Anatomy

Senses

Clúnydd are trichromats, and excel at night vision. This, along with their usually dark fur tones, are hints of their historical nocturnal predatory tendencies.

Coat

Clúnydd coats are very varied, to the same level that feld coats are. They are usually comprised of cold hues such as blues, violets or magentas. White, grey and black also common.

Blood

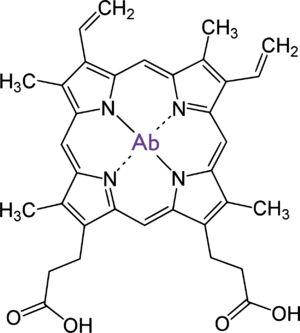

Their blood uses clunocruorin as an oxygen transporting protein, which uses the erdyllic metal clunium. Since it’s very energy dependent, clunýdd's metabolism is slightly faster than a typical carnivore’s, and they require more food to sustain themselves. An advantage this protein has is that it promotes erdyll regeneration, so injuries and the like heal faster. As erdylls already excel in regeneration, this is potentiated in such a way that, were a limb to be cut off from a clúnath, it could be able to regrow fully after a few months or years.

Reproduction

Clúnydd normally reach sexual maturity at around 14 to 16 years of age.

Due to the lack of females of their same species, much like the rest of their clade, clúnydd resort to reproducing via hybridisation with other organisms—in clúnydd's case, felds. This is thought to be the result of an early mimicry mechanism.

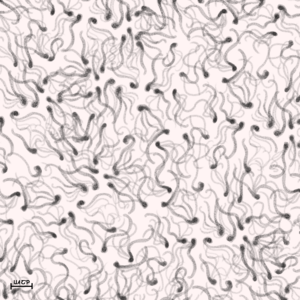

Their silodotes (the erdotic equivalent to cytotic spermatozoa) have acquired cytote-like acrosomes, which aid in the insertion of the clúnath's genetic material into a cytotic ovum.

It’s been found that their genome partly matches that of felds. This is probably due to their peculiar reproduction method, which, after several generations, ended up mixing their genetic information.

The hybridised children can be either clúnydd, dwyllnar, or ferur. Dwyllnar are all males and take the general appearance of a clúnath, but they are neither fully cytotic nor fully erdotic, which may present problems in their development; nevertheless, some individuals may still reproduce. Ferur are the rare female children that, due to hormonal changes interfering with the development of abreggan traits, are only born with horns. This trait is passed down to their children, though being recessive it doesn’t always express itself in every generation.

Culture

Persecution

During the middle ages, partly because of the rapid expansion of the clunocentric Hashan empire, Lady Bor IV of Secyl began a persecution campaign against clúnydd. This campaign persisted throughout her reign and the entire existence of the Queendom of Secyl, which resulted in lingering clúnophobia in the modern day krasnian countries and nearly all dimsin in the area.

Underground dwellings

Many of their cultures still revolve around dwelling underground. As an example, hashan houses are normally built underground, with hallways connecting various rooms within. Sometimes, these complexes can be so large that they become fully fledged underground towns.

Genetics and erdyll studies

Clúnydd have played a fundamental role in understanding how cross-cellular-group hybridisation works. Their very close resemblance to felds has also made it become the go-to entity to justify the theory of erdyllic cytomimicry.

Cosmetics

The thick, dark fur of clúnydd has been sought for since prehistoric times by many cultures. In northern ethian cultures, having a clúnath's coat or a helmet with black horns was considered a sign of strength, and was frequently seen as a status symbol in many communities. In the present day, clúnath fur is not sought after as much. Hunting clúnydd is outlawed in many countries, and selling products derived from these hunts is a common felony across many codes of law.

Films and other media

Clúnydd have appeared in several historical works, mostly being portrayed as terrifying creatures of the night, and frequently taking antagonistic roles. After the publication of the Eryddg a Nghaun however, there was a sudden positive shift in their portrayal. At this time, they were most often portrayed as anti-heroes or morally grey characters. Nowadays, there are virtually no restrictions as to which roles they cover.